An African writer who makes mix tapes of game soundtracks. A Nairobi filmmaker with Nietzsche on his smart phone. A chess champion who loves Philip K Dick. An African SF poet who quotes the Beatniks… meet the new New Wave in Nairobi, Kenya. Part one of our series 100 African Writers of SFF.

Jump to:

- “A little bit of Nairobi does you good”

- Abstract Omega

- About Kwani?

- Alexander Ikawah

- Clifton Cachagua

- Dilman Dila

- Kiprop Kimutai

- Mehul Gohil

- Richard Oduor Oduku and Moses Kilolo

- Ray Mwihaki

- People I did not meet

- Endnote

About that title…

100: Because it’s easy to remember. More like 120 or 130 writers, but many I won’t get to meet. I’ll list as many as I can by location, by social scene. Because people, even writers, succeed in groups.

AFRICAN: Meaning mostly people with African citizenship in Africa, but I’m not going to be draconian. Writers like Nnedi Okorafor and Sofia Samatar are beacons to young Africans. They take an active role in African publishing projects—Nnedi with Lagos 2060 and AfroSF and Sofia with the Jalada Afrofuture(s) anthology, which she helped edit. “African” itself is a dubious concept. I will try to use more precise terms—nations, cities, and peoples.

WRITERS: Will include filmmakers, poets and comics artists. Not all of them have published frequently. Some have only published themselves, but given the lack of publisher opportunities, I think that’s enterprising. They’re still writers.

SFF: Stands for science fiction and fantasy. I use the term in its broadest sense to include generic SF and fantasy, horror, alternative histories, speculative fiction, slipstream, variations on Kafka, fables, nonsense and more.

Some of the most powerful African writing has elements that would be fantastical in the West, but which are everyday in traditional cultures. I use two distinct terms to describe some of the works by these writers—“traditional belief realism” as distinct from “traditional belief fantasy.” The first category includes Tail Of The Blue Bird by Nii Parkes and Kintu by Nansubuga Makumbi. Traditional belief fantasy is actually the older genre, exampled by The Palm-Wine Drinkard by Amos Tutuola or Forest of a Thousand Demons by D.O. Fagunwa.

However, many of these new writers bear the same relation to oral literature that (in a different context), Bob Dylan bore to folk music. Family stories are a springboard to something original, that mashes together any language or material that helps these writers express themselves.

What may be special to Nairobi—and perhaps to countries like Nigeria as well—is the way in which monotheistic, traditional, and scientific belief systems hover in proximity to each other, often without a sense of contradiction.

African writers say that they have to be opportunistic—there are writers who write SFF because it’s an opportunity to publish. There are writers who yearn to write generic three volume fantasy novels, but what they can publish is generic lit-fic—pared-back prose, human relations. In one case that includes the inflight magazine of Kenyan Airways.

Aleya Kassam, a professional storyteller in Nairobi told me, “We don’t have the luxury of genre.” Genre tells you what readers expect, genre provides regular publishing venues. African writers have to write whatever they can publish—at least that is what they tell me in Nairobi. However, as we will see, African artists living in Britain, with access to markets continue to work in many media and to cross genre boundaries.

What I was not expecting was that so many young East African writers would be so involved in experiments with form and language—either returning to mother tongues, or looking at other Western traditions like the Beats or the modernism of 1930s poets like H.D. In the endnotes to this article, I suggest why this might be. The idea, for those who like hypotheses upfront, is that the loss of educational and literary communication in a mother tongue—being forced to fit in with another majority language—creates conditions for literary experiment. The question still to be answered is why this interest in experimental writing seems so distinctively East African.

How this is structured

After a snapshot of Nairobi cultural life, the piece will take the form of interviews with writers, arranged in alphabetical order by first name. This will help give them voice, leave the reader free to also make connections, and also back up some of the conclusions I make for myself. Where appropriate the sections each begin with an extensive quotation from the writer’s work.

Occasional mini articles “About…” will help set context.

The series will continue based on different locations.

I hope academic colleagues find ore to mine. I hope readers of SFF get the basic idea: some of this stuff is entirely off the wall. And well worth finding.

A little bit of Nairobi does you good

Last night in Nairobi I’m with a group called The World’s Loudest Library co-hosted by Ray Mwihaki, whom you are going to meet. WLL is a book swap club, a book discussion club, and a discussion club full stop. It meets upstairs in an Ethiopian restaurant called Dass on Woodvale Grove. I show up on time for the 7 PM start. Mistake. It won’t start until 9 pm and will go on all night. While I wait two hours, we listen to music. The DJ is one of the WLL members and the music is contemporary—I can’t tell if it’s African or American.

So here’s two of the people I met, who for me show what’s special about Nairobi.

Andrew (not his real name) is a white guy from Missouri who got his second degree in Nairobi and now works as a senior editor for a newspaper. He came to Kenya because he didn’t want to end up like other American graduates he knows, biochemists still living in their parents’ garages. There simply aren’t the job opportunities in the USA.

So we are already in the situation where Americans are migrating to Africa looking for work. Right now, these people are imaginative outliers. Point being—things are changing with blinding speed.

Second, meet Laure (again not her name, I wasn’t able to ask if she wanted be quoted). She is a product of the discipline of a Kenyan upbringing. Her parents believed in the creation of a new Kenya, so didn’t allow her to speak local languages. She picked up Swahili and Sheng. She didn’t say but I have a terrible feeling that she is “rusty” in her mother tongue. She thinks that most Kenyans have to learn about four languages and that means they find it easier to pick up languages later in life. That, she thinks, could be a great business strength for African cultures. She speaks English, French, German, Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese and is learning Chinese. She lived for six years in the USA, hated it, and came back with a post doc in robotics. She knows she won’t find work in Kenya and so will move abroad, probably to China.

As one of our interviewees says, “You stay out of Nairobi three years, you can’t write about the place, it’s changing too fast.” That’s Mehul Gohil, and you will meet him too. He’s an outspoken fellow.

Abstract Omega

…is the creative name of Dan Muchina. He’s 28 years old and makes a living as a freelance filmmaker and film editor. The day after we speak he will be filming an all-day musical event at a racecourse, featuring Aloe Blacc. Dan is short, thin, looks about 17 and wears a hoodie that holds down a broad-brimmed baseball cap. I admit, I mistook him for someone much younger, and worried a bit that he could have achieved much to write about. How wrong I was.

Dan started writing a lot of poetry in high school and that evolved into rap. “Then I started creating visuals to go along with the things I was expressing. I fell in love with photography and that evolved into video. A lot of people called what I was doing experimental but I wasn’t analysing, just shooting it, not labelling it experimental or SF. I wasn’t interested. It was the media I fell in love with for what I could learn from it.”

“He writes, directs and shoots his own films. Recently completed are Monsoons Over the Moon, two short films in a series. Both can be seen on YouTube: Monsoons Over the Moon—Part One was released in June 2015 and is eight minutes long. Monsoons Over the Moon—Part Two is ten minutes long and was uploaded in November.”

“People tell me it’s about a post apocalyptic Nairobi. The characters are trying to find a way out of the system and find joy and piece of mind. It wasn’t my intention to do a post apocalyptic story was just what I did at the time.”

“My new project is called Eon of Light and I’m hoping it’s about new life generating where a star fell to earth in a place called Kianjata. Particles from it mix with soil and air and the plants growing there are genetically altered. People eat them and the plants affect human DNA. People begin to be able to communicate with birds and nature. These people are outside the system so a Rwandan style genocide results. The hero sees this on the TV news and realises he is the third generation of such people, raised in the city. He is able to read information in his own DNA.”

I say that touches on a number of African stories: the move from the rural to the city; government violence and inter-communal violence; and the loss of contact with forebears and a connection with something integral.

“That’s the thing with African science fiction. You say SF and people expect spaceships and gadgets, but it’s full of symbols. Africans have always told stories with lots of symbolism. We have always created magical worlds in our stories that symbolize.”

Eons would be a series of short films that stand independently but would be set in Kianjata and the city.

I talk about how the Jalada collective have made local African languages a key topic again. I ask him what language his characters speak.

“They speak a hybrid of odd English, Swahili and Sheng so they don’t use any pure local language. It’s more authentic.”

My eyes widen. “Authentic” is a word you’re supposed to avoid in discussions of African fiction—it’s often used by people imposing their own expectations on writers.

“I haven’t met any young people who don’t speak Sheng. It started with the first generations of people who came to Nairobi and is a mix of languages that developed more in the informal settlements than the suburbs.”

Until 2015, Dan worked with the Nest Collective, which produced a feature film The Stories of Our Lives, written and directed by Jim Chuchu. Dan is the credited cinematographer. The 62-minute film opened at the Toronto International Film Festival and was warmly received. The Huffington Post called The Stories of Our Lives “one of the most stunning and triumphant films of the year.”

The trailer for Stories of our Lives shows Dan’s luminous cinematography.

The link also leads to the range of other activities by the Nest, including the lovely soundtrack to the film.

The film is banned in Kenya. The rumour is that the makers escaped prosecution on the understanding that the film will never be shown there. The film, which tells the story of a number of queer Kenyans, is not, according to the Kenyan Film Board, “in line with Kenyan cultural values”.

He didn’t mention any of that when we talked. Later I Skyped him to make sure I had the facts right. “The filmmakers were in danger of prosecution. The Executive Producer (George Cachara) had been arrested on the count of filming without a license. He was however set free on cash bail. The case was later dropped.” Before coming out as the creators, the filmmakers took out insurance and found secret safe houses in which to hide.

Change of subject.

My Leverhulme grant is to study the sudden rise of African science fiction and fantasy—its roots. So I always ask what people read or saw to interest them in science fiction. Dan lists two cartoons: “Arcadia and the Sun Beneath the Sea” and the series Johnny Quest.

“I loved those when I was a kid. They created other worlds through space or time through which to escape and live in that world.”

I ask him what he’s reading now and he hands me his smartphone.

Some books on Dan’s iPhone:

- Wilhelm Reich, Murder of Christ

- Carl Jung

- Nietzsche, Untimely Meditations

- Poetry of Saul Williams

- Gurdjieff

- Dante, The Divine Comedy

- Edwin Swedenborg, Heaven and Hell

- The Kabbalah

- Nicolai Tesla

- Machiavelli, The Prince

Dan studied Journalism and Mass Communication at Kenya Polytechnic University College, and interned for seven months at Kwani Trust as their in-house photographer.

“In high school I listened to hip hop, but of a particular type, spacey, dreamy, about travelling between worlds, crossing astral boundaries. Aesop Rock, E-LP, Eyedea, Atmospher, and C Rayz Waltz. Those rappers are white so you probably can’t call them Afrofuturists, just Futurist. But I relate very much to a kid in the boroughs of NYC wanting to travel in time and space, nothing to do with him being American and me being African.”

“I wanted to meet someone from a completely different time. Maybe a future generation will stumble on my work and be able to communicate with someone from a different time.”

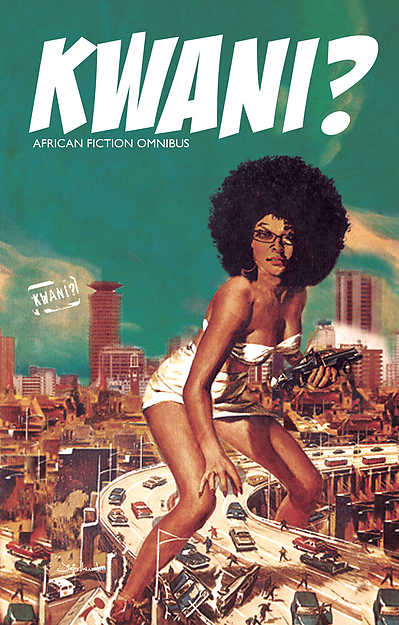

About Kwani?

You will hear a lot about Kwani? (“Why?” in Swahili) in this series. When Binyavanga Wainaina won the Caine Prize in 2003 he set up the company with the Prize money. The company publishes regular, book-like anthologies, individual novels and collections, runs the monthly Kwani? Open Mic nights and sponsors the Kwani? MS Award, which resulted in the first publication of Nansubaga Makumbi’s Kintu and also of Nikhil Singh’s Taty Went West. Kwani? was one of the sponsors of the workshop that resulted in the foundation of the Jalada collective.

Binyavanga was a key figure in the selection of writers for Africa 39, credited with researching the writers, with Ellah Wakatama Allfrey editing and a panel of three judging the final list of the 39 best African writers under 40. Binyavanga is a mainstream figure but he has always defended science fiction and its role in African literature. He did a reading a couple of years ago at the London School of Economics and it got inside his father’s head in a mix of biography and stream of consciousness fiction—it also drew heavily on science for its metaphors: Higgs Boson for unknowabilty, neutrinos (I seem to remember) for people who don’t interact with others.

Alexander Ikawah

Night was the best time to visit Quadrant 7 if you were looking for mem-bits from the 21st. Old men too poor to afford to make money any other way, sold priceless memories for as little as 100 EA$. They sold to me cheaply because I bought memories nobody else wanted. Love, pain, laughter, and happiness, but mostly I bought history. I paid extra for memories of childhood in the late 21st; before the water and energy rations, even before ZEOS itself. I had a modest website where I uploaded them for free, and it was getting quite well known. I wasn’t the only one looking for the feelings we had lost. The vicious gangs that ran the quadrant did it differently though. They almost exclusively bought sexual memories, and then violence, thrills, and intoxication in that order. And if you owed them for food or a place to sleep as most of the old men did, they paid you nothing. They preferred to rip them for quality, erasing the memory from its donor’s mind completely. Gaps in the mind drove you crazy after a while, and the quadrant streets were full of people who had sold too much, wandering the streets trying to relearn things they had known all their lives.

Alexander Ikawah walks into the Decasa Hotel on River Road with a very expensive camera, having just bussed back from Garissa, a northern town near the Somalia border. He was photographing an event commemorating the anniversary of a mass murder at a branch of his own old university. Al-Shabaab militants targeted Christian students as they slept in dormitories—148 people were murdered.

He is outraged that publicity-seeking politicians had hijacked the event. He shows me with toothpicks on the tablecloth how the politicians faced the media and the media faced them, and both had their backs to the crowd.

“The media were performing for the politicians and the politicians for the media.” Tribalism is one of his key themes. Some of the Somali community might have known the attack but there is not much communication with other Kenyans. He believes that privileging English has contributed to cutting off local language groups from each other because only the elites from different language groups truly communicate to each other in English.

To read more on the Garissa massacre, Alex recommends a news story by Nanjala Nyabola.

Alex is a journalist. Also a writer of literary fiction, a writer of science fiction, a poet, a musician, a TV station’s graphic designer, a photographer and a film maker. Artists in Kenya turn themselves to whatever is at hand.

His short story “April with Oyundi” was shortlisted for the 2015 Commonwealth Short Story Prize—the second time he has been shortlisted. He is a founding member of the Jalada Collective, the voice of a new Pan-African generation of writers and important for this series because its third anthology (perversely numbered 02) was Afrofuture(s), featuring contributions from many African writers, including huge names in the field like Binyavanga Wainaina, Dilman Dila, and Sofia Samatar.

He is releasing his film Relay Point Omega online in a month or two (Summer 2016) about a future Nairobi dystopia. It’s 27 minutes long and was premiered at the African Futures event series (a three-city festival of AfroFuturism sponsored by the Goethe-Institut).

The film offers a choice of different endings, designed to be viewed on YouTube, with viewers being able to select their own ending. You can see a trailer for the film here, and coverage of a recent screening and discussion of Afrofuturism can be found here.

Alex has a long history with the experimental literary scene in Nairobi, at one stage being a host for the group World’s Loudest Library. He would issue writing challenges from the Writers Digest website and publish his own responses on his blog.

His SFF stories from this period include “Where the Grass Has Grown,” which you can read on Alex’s blog, about idols and an ancient curse, written in honor of cartoonist Frank Odoi.

“Afropolis,” a story he wrote in 2012 for the Innis and Outis Science Fiction competition, is science fiction by the definition of the term—a picture of a future city of 3000-foot skyscrapers, about a man who buys people’s memories in a kind of bleak Tomorrow Land. He says it is set in a Nairobi with aspects of American culture taken to extremes. He tried—and he thinks failed—to give the SF content a local Nairobi flavor.

“There is a difficulty for science fiction stories as so many of the words and concepts used don’t have equivalents in local languages. Because the writers have to think in English, a lot of African science fiction lacks a unique voice. That was the problem I encountered when I tried to expand “Afropolis” into a novel.”

“Afropolis” remains unfinished, though you can read it here on his blog.

“Some people writing SF based in an African setting transfer the western models almost completely, using only local names and settings and fail to really write about Africa and Africans. In particular, they fail to source their material from local aesthetics, folklore, and oral tradition. Such work always feels borrowed and false.”

Of his fiction, his favorite story is “Sex Education for Village Boys,” published by Jalada, a mainstream story that combines experiences of friends in his home town. It reminds me a lot of the work of Junot Diaz. Here again, the question of language and local voice is crucial for him.

“I imagined the story in Luo and then translated it for readers in English. Which is different from thinking in English and writing in English. I’m quite OK with writing in English but when you are thinking in English, you are outward facing, you are performing English. When you do that you resort to clichés, familiar phrases, tropes, stuff which you think is typically English, and it is a bit stale. If you are thinking in a local language, or in a local version of English, you find and keep your voice.”

This is a familiar theme among a lot of the younger writers in Kenya. They find the work of the older generation of writers either formally conservative or just too English.

“For some time in Kenya you were punished for speaking in a local language except perhaps for special topics or an hour a day in school. You learned Swahili for just an hour a day. Speaking English has become a class thing. Some parents have prevented their children from learning local languages as a sign of status. Even Swahili is not safe from this.”

“For me, this is neo-colonialism. Being taught to think in English, being forbidden to speak local languages, learning concepts in English. This means our intellectuals look to the West. The thoughts and literary works expressed in local languages and for local consumption are regarded as less valuable.

“This class association means that the non-elite segments of local-language speakers don’t communicate with each other and get locked in separate spheres. So the result of trying to make everyone speak English is actually an increase in tribalism among the rank and file.”

At the time we speak, he’s working on “Chieng Ping”—a story set in pre-colonial times about an annual football match between local warriors and the spirits. The hero of the story is the first girl to take part in such a match and she changes the rules of the tribe in favour of women as a result.

“African oral tradition did not have genres per se but just had different kinds of stories. In Western literary tradition SF and Fantasy are considered a niche but they are mainstream in the African oral tradition.”

In the Luo stories he grew up with, magic is every day. “Christianity othered this kind of thought. It was pushed into to a niche because it is antithetical to Christian thought.”

He in fact credits his earliest SF influence as being the Bible, especially the Book of Revelations. “I liked the animals with two different heads and horsemen of the apocalypse. I didn’t want a religious interpretation.” He loved Tolkien, but most especially The Silmarillion, which read like a collection of oral tales or the Bible.

He was particularly fond of Luo traditional stories about Apul-Apul. “I wondered how it was that Apul-Apul kept varying in size and appearance. In one story he could swallow a town, in another be beaten up by a hare. Then I realized that he is in fact a concept, the concept of greed, and I loved that.”

He read a lot of H. Rider Haggard and loved the impossible monsters of John Wyndham’s The Kraken Wakes. As a child he loved Japanese anime, Roald Dahl, and Dr. Seuss. Alex is a Ray Bradbury fan and wants to adapt for film the Ray Bradbury story “The Wonderful Ice Cream Suit.” He is also a great fan of the Nigerian singer-songwriter Fela Kuti.

“Fela started out in English, moved to Yoruba but eventually settled on pidgin. Pidgin is a halfway house, a localized English full of local voice, expressing a range of thoughts. Kuti is able to put philosophy into his song, like oral tradition. His songs are full of commentary, political and social.”

Alex considers himself “a revolutionary writer with a purpose” for whom language is a political weapon. For him, “All writing is rebellious.” Writing science fiction or stories based on traditional beliefs, and re-examining the role of English are all rebellions against the mainstream. Perhaps the most distinctive strand characterizing some Nairobi writers is an interest in experimental fiction. Taken together these elements make these young writers, though all very different from each other, into something like a movement.

Clifton Cachagua

Cars

I dismember grasshoppers

eat their frosty limbs,

hop over the carcasses of cars.

Yes, I need to migrate,

spread this plague, complete the

latitudes they have mapped on my vessels.

Collages of organs:

lying on the grass, I watch myself on Mars.—From The Cartographer of Water (Slapering Hol Press)

Meja Mwangi, last seen here a long time ago, disappears into Sabina Joy with an amputee prostitute who offers him an hour’s worth of conversation in Gikuyu—no longer spoken here—for ten times the normal rate. She holds his hand tight and smiles like two moons, blush on the cheeks. He disappears inside her, never to be seen again. Some people will stalk his grave and spend fifty years waiting, fasting, praying. Cyborgs will find them there and eat their intestines alive. Alive. Pick, roll, unfurl them in their hands like cashew nuts. He will never come back; the sons will never come back to their mothers. The mothers will have forgotten they have sons.

—From “No Kissing the Dolls Unless Jimi Hendrix is Playing” from Africa 39, edited by Ellah Wakatama Allfrey

Jamaican-born novelist Stephanie Saulter is a friend but I was annoyed when she started to read Clifton Cachagua aloud for the London African Reading Group (ARG!). That was what I was going to do! I thought I was so original. If you are a writer, reading Clifton Cachagua aloud might well be irresistible.

The story appeared in Africa 39 and is called “No Kissing the Dolls Unless Jimi Hendrix is Playing.” It doesn’t make any sense, at least conscious sense, but it rings true because it comes direct from the subconscious, like Alice in Wonderland or Miyazaki’s Chihiro. Only it’s sexy, queer in the most profound sense of tapping into the source of sexuality, and of course, it thrills to Nairobi in all its energy and occasional cruelty. It is an example of what Clifton calls “the continuous fictional dream.”

His being selected for Africa 39 means Ellah Wakatama Allfrey and Binyavanga Wainaina considered Clifton to be one of the 39 best African writers under the age of 40. He’s also the winner of the Sillerman Award for new African poets. This resulted in his first poetry chapbook The Cartographer of Water being published by Slapering Hol Press in the USA with support from the African Poetry Book Fund and many other bodies.

His poetry is tinged with fantasy and SF imagery, as is his short prose fiction.

He’s a fan of the Beats and the Dadaists, the Surrealists, and modernists like the rediscovered poet H.D. He recited a chunk of the opening of Alan Ginsberg’s “Howl.” And he is devoted to a strand of Kenyan writing, a wilder and more experimental tradition than much of African writing. This goes back to his first experience of books.

“I came into reading by a weird way. I was 11 years old, a dreamy kid. It was after catechism class in the evening at Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Kariobangi. I was passing by the dispensary—mission churches would build a retirement home or something, this church had a dispensary—and I found a green paper bag there with novels inside, but they had all come apart at the seams. They were big books, but they were all mixed together. There was a novel by a Nairobi crime writer John Kiriamiti, and the book Going Down River Road. The third one was about Kiriamiti’s girlfriend My Life With A Criminal: Milly’s Story. He writes about fucking her but in her point of view and I got such a hard on. I confused all the novels as one. It’s why I can’t write traditional narrative. That was my first time into prose getting so excited, finding these things so beautiful, so Kenyan, so Nairobian.”

Meja Mwangi is a character in “No Kissing The Dolls” and that story is set in part on River Road.

“Going Down River Road is one of the definitive texts of my life. I’m very concerned about class and privilege in Nairobi. I don’t know where it comes from. Mwangi made the city possible for me, possible to think of it as a character, to think of downtown Nairobi as a kind of possible place, made a kind of consciousness possible. Nairobi spans miles, but the Nairobi of the 70s and 80s belongs to River Road and the town centre. I do have a kind of love-hate relationship with Mwangi. I am critical of the idea of Nairobi existing in such a small space. Nairobi is huge, there are all kinds of people who live outside downtown. A lot of people confuse Nairobiness with Kenya-ness but they are not the same thing.”

Another hero is the Zimbabwean author Dambudzo Marechera. He is the author of the award winning story collection House of Hunger and the dense, allusive novel Black Sunlight, which was banned in his native country. That novel’s mix of rage, depression, violence, self-hatred and self-destructiveness is toxic but overwhelming.

Cachagua says, “I like his poetry better. Marechera was way ahead of his time. In poetry I can’t see any equivalent to him. A lot of people talk about his prose and his life, how he fucked around and fucked up. I don’t care about that biographical stuff. I fell in love with his poetry and his prose. He made a certain kind of African collectiveness possible.”

Collectiveness is a key theme of how Nairobi writers behave—Jalada, the Nest, World’s Loudest Library, Manure Fresh… and of course Kwani?. Cachagua works for Kwani? alongside its main editor Billy Kahora.

“My friends want to kill me. It’s the best job in Kenya. I help with poetry, I do a lot of the commissioning work, structural edits, administrative work and maybe I will work on a poetry anthology. ”

He is also one of the founders of the Jalada collective.

“We all met at a workshop sponsored by Kwani?, the British Council, and the Commonwealth Institute. It was taught by Ellah Wakatama Allfrey, Nadifa Mohammed and Adam Fouldes.

“We needed an alternative to mainstream voices. We were all born after 1985 and we all studied here. We are not returnees from the diaspora, we had not been students in the West or South Africa. The farthest I’ve travelled is to Uganda or Tanzania. It wasn’t a rebellion, it was about possibilities; possibility means more to me than rebellion.

We knew we had voices, we were desperate to get published and to collaborate as well, but we had such few places to do to that. We asked why don’t we establish our own space? One of the fundamental ideas was peer review, don’t just accept or reject but how you can improve the work. So come together and review each other’s work.”

He is at work on a surrealistic novel but says that after that he will focus on poetry.

“I’ve always been interested in the nonsensical, especially the nonsensical body, the body not making sense, the body mangled up. It’s subconscious and I haven’t examined it enough. I’m still in a place to be really honest, I don’t actually believe I’m a writer. I’m trying to work my way to being a writer so thinking about the subconscious. It’s a lifetime thing, this finding out.”

Read Clifton’s short story “Falling Objects from Space” on his blog.

Dilman Dila

With Kwani?, Jalada, the Story Moja festival, Fresh Manure and so much else happening, Nairobi has become an arts pull for all of East Africa.

While I was there Dilman Dila also visited. He’s the author of one of Africa’s first single-author SFF collections A Killing in the Sun (the lead story was shortlisted for the Commonwealth Fiction Prize!). He dropped by and ended up staying at the Decasa Hotel as well.

Dilman makes a living as a screenplay writer and filmmaker. He’d just finished a documentary about the making of Queen of Katwe, directed by Mira Nair (the director of Salaam Bombay!) and starring David Oyelowo and Lupita Nyong’o. With the money from that documentary, Dilman financed his next self-directed feature film, Her Broken Shadow.

His interview with me is reserved for later in this series, after I’ve been to Uganda to see the scene there for myself. So more from Dilman later.

My good fortune in Nairobi was to have Dilman vouchsafe to my tablet the first cut of Her Broken Shadow. Seeing it contributed potently to my impression of Nairobi.

We adapt Philip K .Dick novels and turn them into action movies. Dilman’s movie is a sophisticated piece of metafiction that crosses Philip K. Dick with Samuel Beckett, alternative realities and monologues.

Her Broken Shadow is about a woman in a near East-African future, trying to write a novel about a woman in the far future—who is writing a novel about her. The two women are played by the same actress, but with such different ways of moving and being that it takes some people (me and a couple of others) a while to notice.

Fiction that is about fiction—especially when the shattering revelation is that we are reading a story (Really? I had no idea!)—is possibly my least favourite genre. I was knocked out by the film’s ambition and integrity.

SPOILER: The genius of the thing is that there is a good, plot-level SF reason why they end up in each other’s novel. If Dilman had scripted The Matrix, I might have believed it. And just when this story seems all sewn up, the very last scene overturns everything again, and we hit rock bottom reality.

It is about being alone. It’s a satire on writing workshops. It’s a vivid stand for the future being African; it’s a philosophical conundrum; it’s a two-hander for one actress, each character locked claustrophobically but photogenically in a small location talking essentially to herself. There is a murder. Or are there two murders? Or none? What’s imagined?

It also has the best hat in the history of cinema.

Another auteur-film by Dilman—not a fantasy—is the 18-minute, Hitchcock-like What Happened in Room 13. It’s the most watched African film on YouTube:

I am left with the question—why is East Africa a home of not only of experimental, literary science fiction but experimental, literary SF film?

Kiprop Kimutai

One day they will all know that I am Princess Sailendra of Malindi. They will know that that palace on the rocky ledge at the corner of the beach is mine and that it is made out of coral and red marble. They will know that my bedroom inside the palace is scented with jasmine and lit with rose scented candles and that the window faces the east so that I can be woken up by the sun. They will know that in the morning I only have to snap my fingers and all these male servants with rippling muscles and washboard abs will carry me to my bathroom and lay me in sudsy water; they will feed me grapes as they rub honey all over my body. One day I will just close my eyes and march Hitler-style across the beach and they will part the way for me. They will say “kwisha leo, Sailendra is among us” and faint on the shore. Afterwards they will scoop my footprints, pour the sand into glass jars and display it in their living rooms. One day.

—From “Princess Sailendra of Malindi” from Lusaka Punk and Other Stories: The Caine Prize Anthology 2015

I went to Nairobi with no expectations. But I really, really had no expectation of meeting someone who is a Jane Johnson fan.

Jane Johnson was my editor at HarperCollins. She’s the woman who for years steered the Tolkien legacy through success after success. As Jude Fisher she wrote a series of fantasy novels drawing on everything she had learned as an editor. And they are Kiprop Kimutai’s favorite books.

“I love the Sorcery Rising series. I think her language is beautiful and I love that heroines are not beautiful.” He used to go to book exchange clubs and find fantasy fiction when he could—through them he’s become a fan of Guy Gavriel Kay, of Stephen King’s The Dark Tower, and of course George R. R. Martin.

But his earliest exposure to SFF was not through comics, or shows on TV but through programmes and books on ancient kingdoms and history—Egypt or Great Zimbabwe and their mythologies. He loved reading about kingdoms and imagining life in them or reading about their gods or myths of origin.

He especially loved the Aztec civilization. He read Gary Jennings’ Aztec series: “He used the authentic technology of the Aztecs, but didn’t get into the mind of an Aztec, but sounded like an anthropology professor.” Kiprop found Aliette de Bodard’s Obsidian and Blood more convincing and imaginative.

“It’s fantasy I burn to write,” he tells me. Instead, he keeps getting drawn into writing mainstream fiction.

He was a runner-up in the Kwani? manuscript prize after Nansubuga Makumbi’s Kintu. “So my novel The Water Spirits is going to be published by them. It’s almost a fantasy novel. A boy believes that if you catch and hold a water spirit she will bring good fortune. But he captures and holds a real girl instead. It’s being edited by Ellah Wakatama Allfrey and will be out this year. Being edited by Ellah is eye-opening.”

He was selected to attend last year’s Caine Prize workshop in Accra, Ghana, held before the award ceremony in Oxford in July. The story he workshopped there, “Princess Sailendra of Malindi,” was anthologized in Lusaka Punk, the Caine Prize anthology for 2015. It was then reprinted with luxurious illustrations in Msafiri—the in-flight magazine of Kenya Airways.

It’s another mainstream story about fantasy—a young heroin addict imagines she is a beautiful princess of a distant land. The yearning to be a beautiful princess in a lovelier body reminds me just a bit of a transsexual imaginings. The heroin addiction makes the whole story hallucinogenic with a layer of almost religious imagery laid on top of a story of a lost brother and ruined lives, with a drug addict sage.

In an in-flight magazine. Life is so much more interesting when literature is not trapped in genre.

Another one of his stories, again traditional belief realism grew out of a famous workshop. “Evening Tea with the Dead” was first published in A Handful of Dust: Stories from the 2013 Farafina Trust Creative Writing Workshop, (2013, Kachifo Farafina).

Kiprop is a founding member of Jalada and suggested the theme for their first anthology, Jalada 00—insanity.

His story in that issue, “The Gentle Man from Iten” is lit fic—you are meant to work out character and backstory from what you shown. Why are people being quite so cruel to an insane woman who has wandered into Tala’s store? Why is every one so angry at Tala for being too nice? Especially his wife?

If you are not Kenyan, it will take you a while longer to work out the context—Tala is Kalenjin-Kikuyu mix, the insane woman is Kikuyu and it is the 2008 election when the two peoples are slaughtering each other. But Tala remembers his Kikuyu grandmother, who sang a beautiful song about loss.

Kiprop’s mainstream work yearns towards fantasy. In one uncanny moment for both us and the gentle Tala, the insane woman sounds like she just might be possessed by the spirit of his grandmother.

“The Gentle Man from Iten” is available to read online, along with the rest of the first Jalada anthology.

“I am an ethnic Kalenjin but I don’t speak that language in a sustained way, I was always speaking in English or Swahili, and never sustained myself in one continuously. My grandparents would speak nothing but Kalenjin for weeks at a time. My mom was born in 1948, my Dad two years before. In the village people wore skins, worshipped the sun. Western clothing, education and Christianity came in during my grandparents’ lifetime. They witnessed a world that died, a catastrophe that no one invited in. We have now made English our own language, and are making new languages.

Our English is influenced by Swahili, our lingua franca. Kenyans’ love of African cinema means expressions from Nigeria are arriving. Kenyan English is getting expressions of its own like ‘help me a pen’ instead of ‘Can I borrow your pen please?’”

The Afrofuture(s) anthology came after the anthology on insanity and a second about technology and sex called Sext Me.

“Afrofuture(s) was about our people imagining alternative realities for the future. For example, Africans as colonizers. For us the oceans never belonged to us.

“Again, it was a difficult edit. It was often hard to work out what the ideas in the stories were, hard to work your way into the world. It’s the science fiction writer’s job to make us believe and understand.”

Kiprop is a very friendly, complex person. He has made English his own; he is part of a concerted effort to revive local languages. To me, he talks about his love of generic fantasy. In Jalada 00, he describes himself as “a writer haunted constantly by his ancestors who demand to have their stories written” and says his favorite writer is John Steinbeck. He has a list of all the agents in England or the USA he wants to target.

I talk to him about an interview I did with Tade Thompson, Biram Mboob and Chikodili Emelumadu back in London. I’d suggested to those three writers that much of African SFF was about resolving the contradiction between traditional beliefs, Christianity and science. Chikodili laughed at that and said that for Nigerians, there was no contradiction—the different belief systems co-existed.

When told that story, Kiprop said, “Western fantasy is about that tension. Our fantasy is about the LACK of contradiction.”

And he is hard at work on a three-volume epic fantasy novel.

Mehul Gohil

Cephas and Erabus are squeezed in the crowd. There is bad breath and aftershave here. Shoulders rub against each other and there is warmth in the ice-cream wind. Cephas steps out of the crowd and walks into the road, into the rain and in between cars that are stuck in a jam that will be measured in half days. He looks at the sky and what he can see. It’s not gray, it’s not blue but it has headlines all over. It’s black and white. They are floating in the sky. The skyscrapers are reflecting them but who knows if its an optical illusion because in the crowd they are all reading The Daily Nation and Standard on their iPhones and the echo effect in the sky escapes them. Blind spot.

‘Kenyan Writer Dies of Book Hunger’.

—From “Elephants Chained to Big Kennels” published in African Violet and Other Stories: The Caine Prize Anthology for 2012

Mehul Gohil is a stone cold science fiction fan whose brilliant writing style has ended up corralling him into the literary mainstream of African fiction.

Like Clifton Cachagua and Shadreck Chikoti, he is one of the SFF writers selected for Africa 39, a collection of work from the 39 best African Writers under the age of 40. He was long-listed for and invited to the workshop attached to the Caine Prize of 2012. He’s tiny, thin, tough and talks like a character out of Martin Scorsese’s film Goodfellas.

He is breathtakingly direct about a previous wave of mainly West African writers.

“I wouldn’t consider them African writers. They are more like white writers in the language and structure of the stories. Nigerian writers all sound like they were born to one mother. Kenyan writers are born to different mothers—they all sound different: Wainaina, Clifton, me, Moses, Alex.

“There are many good writers but they go away and live abroad. If you stay away from Nairobi for more than three years, you lose touch with language and culture going off. If you leave to go live in the diaspora you really won’t know. The dynamics are changing so fast. You are going to be out date quickly.”

He himself is a native of Nairobi and writes like one—his stories are stuffed full of details of Nairobi streets. And his non-fiction, too—for proof, follow this link to an article about hunting books in Nairobi.

“My great-grandfather was Indian but when I go to India I feel a stranger. Many Indians have been here for generations. Gujerati is an African tongue.”

There is soon to be a bonus language issue of Jalada, and “Farah Aideed Goes to Gulf War” is being translated into Swahili by Barbara Wanjala. Mehul can speak Swahili but not write it.

“Technology makes the local language thing more current and interesting. It offers more ideas about how to save local languages but also how to publish them or use them. English by itself looks binary. People in Nairobi speak a fusion of languages.”

He gives an example from his own story “Madagascar Vanilla” of how a mix of languages can lift monolingual texts. The story appears in the second Jalada anthology on technology and sex, Sext Me (Jalada 01)

“People are always saying that sex is like the ocean. I wanted to make it more like space, with water from Enceladus. I needed a word for the sound of an airplane. I couldn’t find a good one in English, but it was there in Swahili, from the Arabic—zannana. An airplane zannanas.”

Mehul got into writing late. He started in 2009 with a story about chess. He was playing for the Kenyan National team, and has a FIDE title. (Indeed, a month after my visit he would win the 2016 Nairobi Open Chess Tournament.) To please his girlfriend, he entered a Kwani? writing competition called Kenya Living. He wrote the chess-themed story in five hours and submitted on the deadline day, not expecting to win. The story, “Farah Aideed Goes to Gulf War,” won the competition; you can read the full story at the link. His writing began to attract a lot of attention, going to the Caine Prize workshop in 2012 where he wrote his first SF story and on to a the 2013 writing workshop where the core of the Jalada collective met.

“We hardly knew each other but we turned out to be a powerful force individually and collectively. We had all these old guys making the decisions and we wanted publishing control. We said let’s run something. We had a long discussion over emails. We had people from all over Africa and even the USA involved.”

Focusing the third anthology of Jalada (Jalada 02) on Afrofuture(s) was his idea.

“I had read a lot of SF since I was a kid. The others weren’t that interested at first, until I kept on writing and sending emails and in the end most of them went along with it. It turned out to be the most important issue after the Language issues.”

He acknowledges Sofia Samatar, who acted as an editor for the anthology. “She edited the pieces that got through the selection process, and really helped publicize this issue. Nnedi Okorafor and her are the first women on the moon. But I wonder what follows when a million Nairobi women have also been to the moon.”

“When I was ten years old the mall had a secondhand bookshop. It was my birthday and my dad said pick what you want. I wanted big thick books, not the picture books. The first books I picked up were Philip K. Dick, Samuel Delaney and Fritz Leiber. I really thought Leiber was good and I understood Dick even as a kid. I liked that in Dick no one is surprised by the new technology—it’s normal and everyday. The spaceship lands and no one cares. Right now I love Ann Leckie, Alastair Reynolds and C.J. Cherryh.”

He enthuses (like others on this trip) about Nikhil Singh’s Taty Went West, an SF novel that premiered at the Africa Futures events, published by Kwani? “It’s a kind of cyberpunk but it keeps pulling forth fresh stuff with fantastic prose style and a wild imagination. It’s going to be big, just excellent.” He takes me on a Nairobi book hunt but it turns out that Taty has sold out, even in Kwani?’s offices. He tries to give me one of his copies.

Mehul is very proud that Jalada publishes poetry as well as prose. He namechecks Shailja Patel and Stephen Derwent Partington, and goes on to say “That means Jalada publishes something unique—science fiction poetry.” When I point out in the interests of accuracy that there is a long American tradition of science fiction poetry, I feel a bit mean.

“Nigeria had some groundbreakers a while ago. But Leakey says human beings won’t evolve any more because we travel too much. We don’t live in isolated pockets so we don’t branch out into different streams. We become too homogenous. Nigeria is one big family; it has become too homogenous—everything written there sounds the same. Nairobi is isolated and evolving in our own terms. Nairobi people just want to be different. I must be different from every other family. Nairobi women must be different from other girls, they must do something different with their hair or fashion.”

I don’t think it’s just Nigeria that has become homogenous—it’s the world. Middlebrow lit fic in standard English is prevalent wherever publishers want to sell to a world market. Mehul doesn’t speak of the SFF bomb being set off in Nigeria by Chinelo Onwualu and Fred Nwonwu through Omenana magazine. Nigerian diasporan author Tosin Coker not only writes science-fantasy trilogies in English but children’s books in Yoruba.

Nairobi is nearly a mile high. It’s cool and rainy, without mosquitoes for much of the year. It has an international airport but otherwise it’s quite difficult to get into—matatus from the country queue for hours in its narrow streets. The world’s books are now downloadable onto smartphones, but Mehul and other Nairobi writers grew up in a formal, old-fashioned educational system in which beloved books were trophies to be hunted. It’s entirely possible that it’s cooler to be a reader in Nairobi than in many places.

I think Mehul’s right that Nairobi is evolving its own distinct stream. I wondered why I felt so at home in Nairobi with these writers. I think it’s because they remind me of New Worlds magazine, a product of London in the 60s, a bit of a backwater, where a bunch of talented people cut off from American fandom and its SF magazines happened to coincide and started to publish themselves, crossing SFF with the experimental literature of a previous time.

Meet the new New Wave.

Richard Oduor Oduku and Moses Kilolo

Three feet from where Tika’s mama stood was a blank LCD screen powered down from the ceiling. The screen seemed apprehensive, waiting for the signal to speak to the trapezoidal table where Tika fidgeted with TV, Projector, and PolyCom remotes. All four people were well within the camera’s vision. The lighting was sombrely tuned. The furnishing was that of a cockpit without consoles. All were sweating.

This was the best Single-Point Video Conferencing room that one could set up with the right amount of money and brains. Fabric panelling on the wall and acoustic perforated tiles deadened the pitch of the Pastor’s voice. Tika’s eyes circled the room, looking for missing connections before signalling the giant projection screen to life. He was proud of what he had done. Two VGA Projector Inputs hung at the far end of the table. He fixed them and switched on the light control and the projection screen switches. White light directed four peering eyes to the LCD screen projected on the wall.

Marry me. He had said Yes to Annalina because there was no incentive to say No. He loved her. She loved him. That was all. He wanted a wedding, but not a traditional wedding. Hidden in the midst of tens of icons on the desktop was a shortcut to eNGAGEMENT, a virtualization software. Tika started the program and Logged In. He was directed to eNGAGEMENT.COM—the virtual space that created virtual wedding videos and streamed them. For Tika, eNGAGEMENT was like any other video game, only the characters were him and Annalina and the game was their wedding.

—From “eNGAGEMENT,” Richard Oduor Oduku, Afrofuture(s), Jalada anthology 02

The alleyways and cobbled streets. Cathedrals that stood distinct with crosses illuminating them with bluish white light. A light that grew brighter when looked at. A river ran from the north and meandered through the middle of the city to form an estuary in the southwestern sections. The boat men still cast their nets, and outside resorts bonfires were lit, men dancing around them. The concrete jungle was mostly in Nobel Central where the mayor’s office stood. There were many interspersed gardens of mythical beauty, growing the roses, almonds, lilies, daisies and other delicate plants that ran instinct in the other world where beauty and art were banned.

It was the revolving lights in the distance that made me come to that tower. We were never allowed to go near them. I desperately longed to be there. Close to the outer edge of the city. They shone bright like miniature suns, blinding anyone that went near these outer walls. Only a handful of people knew what that wall was made of. But stories went around. Saying it was made of impenetrable glass a hundred meters in width. The secure world that fed illusions to those outside, kept Imaginum invisible. For outsiders Imaginum could be anywhere. They searched the depths of the Sahara, under the Indian Ocean, and sent satellites even in the sky.

—From “Imaginum,” Moses Kilolo, Afrofuture(s), Jalada anthology 02

If it wasn’t for Jalada’s Afrofuture(s) anthology, Richard Oduor Oduku and Moses Kilolo might not have written science fiction.

They are the administrative core of Jalada’s publications. Moses is the Managing Editor; Richard is the head of its Communication and Publicity Team. Before Jalada, Richard’s favorite reading was The New Yorker while Moses’s was the UK literary magazine Granta. Indeed Jalada has been called “a Granta for Africa”. Its use of topics or themes to inspire unexpected writing certainly resembles Granta—though Moses denies this.

Jalada publishes two themed anthologies a year, and Afrofuture(s) was issue 02. Richard’s story “eNGAGEMENT” concerned a near-future wedding. It’s a sign of how radical the Jalada collective can be that it would not have been out of place in the previous anthology Sext Me—about the impact of new technology on sex.

Moses’s story for Afrofuture(s) envisions a defensive utopia, a city-state into which artists have retreated and screened themselves from the world.

Moses: “The city is invisible to anyone outside it, surrounded by rays that mean if you look at it, a bit like a mirror, you see something else, a landscape a bit like a reflection. I wanted to show the importance of imagination and creative work. If we didn’t have that, what kind of world would we live in? In this story, Imaginum exports creative products to other cities, but other cities feel their existence is meaningless without art of their own, so they want to conquer Imaginum.

“It was my first foray into science fiction so I wasn’t thinking of technicalities. I was more interested in telling a story, and I hoped it would fit in. It was more a utopian story than dystopian. I think Africans are more interested in utopia.”

What is exciting them most right now—now being April of 2016 when I met them at the Alliance Française café—is their Languages programme. Their Language issue published in March was based on a previously unpublished fable written in Kikuya by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. The story was then translated into 33 local languages.

Richard: “The English translation, ‘The Upright Revolution: Or Why Humans Walk Upright,’ had words such as ‘democratic’ and ‘egalitarian.’ When translating the story to Dholuo language, I realized that these words do not have direct translations in my mother tongue hence I had to find a way of preserving the ideas through other words. It is in the same sense that Luo worldview only has a single word, ‘piny’ which translates to either a country, world, earth, or universe.”

Why was the Language programme necessary?

Richard: “This is a political issue. At independence we had lots of local-language books, plays, poetry, but the political system saw local languages as a threat to the state. Sometime in the 1960s publications in local languages were banned. Fiction came to be imagined in English and written in English.”

Moses: “We’ve been raised to speak and write in English. Do we ignore mother tongues to the point that we destroy them? How can we use these languages, engage with them? I‘m a Kamba speaker, but I am rusty in reading and writing my own language. The only things in it to read are the Bible and HIV leaflets.”

Like Alex Ikawah, Richard is a Luo and could really engage with Alex’s “Sex Education for Village Boys”: “I felt I KNOW this; I’ve been through this. When we imagine some of our stories in English, we miss out on certain delightful elements or phrases that only exist in our mother tongues.”

Moses: “There are things that can never be thought in English. English is limiting your expression.”

English in not even the only lingua franca for communication in Kenya—Swahili is the other national language, but fiction in Swahili is hard to find.

Richard: “Instruction in Kenyan schools is predominantly in English, with Swahili being taught as just a subject. Swahili grew from the coast, an offshoot of the interaction between the peoples around the coastal region and Arabs. Swahili is the most popular language, the language of business and social interaction. Now written Swahili is largely school texts; there is very little access to Swahili literature of a personal nature.”

Moses: “Yet it has a long history of literary production on the coasts.”

Richard: “Poems that are still read after four hundred years. Some of the work is fantastic.”

For anthology 04, Richard wrote a story in Luo and then translated it into literal English as “Tribulations of Seducing a Night Runner” word for word, to see what the effect would be.

The result is a radically destabilized English that is, in my view, far more pungently Kenyan than the African writing I usually get to read in England.

The world is broken, son of the lake. Add me a little chang’aa as I tell you this story. Min Apiyo, add us patila here. Life is short my brother, let me eat your hand today.

One day we set out for a funeral disco. We were young and our blood was hot. It was already dark, but we tightened our buttocks that we had to go and dance. So we set off. It’s raining like Satan but we insist that once a journey has begun there is no turning back. We go and the rains beat us. We go and the rains beat us. Omera we were rained on like sugarcane. By the time we reached the disco, we are as cold as a dog’s nose.

Richard: “Expressions like ‘squeezing your buttocks’ didn’t make sense in English even in context.”

Moses: “We wanted to see how something contained in one language would show up in translation into English.”

But being both a writer, and administering Jalada is tough. They have to divide their time among the collective, earning a living, and producing their own writing.

Moses: “I freelance a lot, doing a lot of different things for different media outlets, for PR and advertising. I’m in the middle of a novel, but it goes back to finding time for my own writing. Jalada is in a phase of growth that requires we put in a lot of time. “

Jalada’s publication process is quite special. The founding members consulted by email for about a year to think through what they wanted to do and how to do it.

Moses: “We were fed up with magazines that never responded or which gave no feedback. We wanted to be different, more inclusive.”

Jalada combines aspects of a writers’ workshop—the members write for each anthology and critique each other’s work, and members pay an annual fee. Jalada also invites other writers to contribute or edit. Finally, the project nurtures writers who are not members, giving them some feedback on their stories. Across Africa. In a range of languages including French and Arabic. It’s a co-operative approach that is not only pan-African but reaches out to the diaspora in the USA, the UK—as far as Khazakstan.

Welcome to the future.

* * *

After the interview I walk with Richard and Moses to the Phoenix Theatre for the Kwani? Open Mic Night. A local journalist comes with us, interviewing Richard and Moses as we stroll. They have to miss the event to make another interview, but I’d arranged to meet Clifton Cachuagua and we settle in for a night that will include a tour of River Road and in Clifton’s case, with him being arrested for walking home late at night.

The Mic Night confirmed what the writers had been saying about languages. Only about a quarter of the material was in English. Some of it was influenced by rap and recited in an American accent. The lead performer from Rwanda also performed in clear American English. The crowd was enthusiastic, driven by the dynamite compere, but I have to say, their response to English language material was relatively muted. It was the local language stuff that got the whoops and hollers and comic double takes. I heard a bit of Arabic, I caught some passing English phrases, but what was in the mix—Sheng, Swahili, or local languages I have no way of knowing. The biggest response of the night was to a family musical act with a young kid who looked five years old who sang the chorus “Jah Bless.”

About the only words I could understand. Somehow, it didn’t matter.

A Note about Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and Chinua Achebe

It is no accident that Jalada chose a story by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o to start their Language project. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o is perhaps the most famous African proponent of fiction in local languages. He and the Nigerian Chinua Achebe, who did advocate writing in English, are often cast as being opposite sides of a debate. In my simplicity, I supposed that Jalada might be re-opening the wa Thiong’o/Achebe debate. Beware of any binary—truth is never that simple.

Chinua Achebe is responsible for wa Thiong’o being published, and his advocacy of English included bending it to your will and using local expressions to dislocate it. Writers like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie are regarded as following his footsteps, but again, beware simplicities.

More on Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Chinua Achebe, language, and the African novel can be found in this New Yorker article by Ruth Franklin.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s Decolonizing the Mind: The Politics Of Language In African Literature (1986) is pretty darn convincing though its Marxist terminology feels summarized—NOT wrong, just sketchy and predictable. Writing in English, in English forms, makes your work an adjunct to European literature, perhaps a means of revitalizing European languages and fiction—but what business is that of yours if you are African? English is the power language of the new African bourgeoisie who inherited from the colonizers. States don’t need the languages of colonization to unify—the peasants and working class make new lingua franca of their own like Sheng, Swahili or Pidgin.

“A Statement” at the beginning of the book maps out his own future writing strategy, one not dissimilar to Richard Oduor Oduku’s or Alex Ikawah’s. He described Decolonising The Mind as:

… my farewell to English as a vehicle for my writings. From now on it is Gikuyu and Kiswahili all the way.

However I hope that through the age old medium of translation I shall be able to continue dialogue with all.

That’s what he did. Wa Thiong’o’s most recent novel The Wizard Of The Crow (2006) was translated by himself from his Gikuyu original. It also draws heavily on traditional storytelling and includes absurdist and magical elements—and could even in a pinch be claimed as African SFF by our definition.

Ray Mwihaki

I walked with them to the boat stand. They didn’t seem to mind my presence or maybe they didn’t see me. The thought of invisibility made me smile. I was living vicariously through them. The thought and anticipation of their suffering fed my innermost hunger. This was happiness greater than I had felt ever before and it was only getting better. Now that I had tasted the beyond, I appreciated life and fed on the miseries of life. The one thing I craved from humanity was recognition. No one left a plate out for the unseen. I wanted them to scatter in my presence, to notice me in the least. To leave me little sacrifices to ward off my evil. The movies had lied to us. The living did not feel a sudden shiver when we touch them or walk past. They walk through you and never laugh at the jokes you work eternity to come up with. Good thing is, we eventually get the last laugh.

—“Soul Kiss”

Ray Mwihaki’s favorite music is the soundtracks of old gang-related games—the kind that used 40s to 50s jazz. She makes mixtapes of them. She is much influenced by Datacide, a German website that publishes papers, discussions or stories. “It’s a controversial, grungy publication, really heavy with no filters, nothing polished or pretty.”

Ray is the manager and sub-editor of Manure Fresh, the first hardcopy publication of the group blog Fresh Manure.

Ray wants Manure Fresh “to rival the standards set by Jalada or Kwani? but have stories that don’t fit, less polished stories, we want a rawness.” Clifton Cachagua says, “If you want the most experimental writing in Nairobi, then get Manure Fresh, the book.”

The book has a title of its own, Going Down Moi Avenue (a reference to Going Down River Road by Meja Mwangi). The first issue featured a story written entirely in Sheng, the local mixed language—part of the general impatience with writers who focus on the needs of Western publishing. Ray’s own story was about an underground club that you find by searching for clues and messages around Nairobi. You will have to come to Nairobi to read it, however—it’s available only in hard copy.

Ray’s a current co-host of the World’s Loudest Library, an organization that has in the past been headed by Alex Ikawah and Clifton Cachagua.

“WLL is the mother of Manure Fresh that grew out of our answers to questions that came up during a particular WLL. WLL is a question party. It’s a community. It is the world’s Loudest Library because through the book swap and book drop movements, we are visible and discovered. We hope we have the world’s largest roving library. It’s a party more than a club, we commune with our questions and homegrown music. We are working on a sound system.”

A slide show about WLL and related book exchanges can be found here.

Ray’s own fiction overlaps with the horror genre but plainly owes a lot to African traditional beliefs.

“Mom used to tell us stories that my grandparents told her. I think she felt there was a void to be filled—her parents had died… They had told stores with mystical or magical elements. Kikuyu folk stories have a lot of ogres. Oh God I used to be so scared of them, I would even refuse to eat. And Mom would say— ‘and you, you will finish your food.’

When I was seven, we moved from Nairobi back to a village 20 miles away. It was a rural setting with rural dynamics—if you get no rain it is because your village is cursed. I heard older stories, random stories that have influence on how I see things, directed a lot of my writing and thinking. A story of mine, “Witnessed The Sacrifice” about a little girl waiting to see a monster that comes to cleanse the village every five years. She could warn other girls; she knows it is coming, but she doesn’t because she wants to see it. That story is basically set in our village. There were many things that ruled the place we lived that if we talked about, it would be bad for the gods, bad for my grandparents.”

But the implication is that the monster is also in some way her daddy, preying on village girls.

African SFF can seem to be a boy’s club at times—which is strange when so many of the writers who have had the biggest impact in African speculative writing are women: Nnedi Okorafor, Sofia Samatar, Lauren Beukes, Helen Oyeyemi, Nansubaga Makumbi, or Chinelo Onwualu who also is co-founder of Omenana magazine.

Ray Mwihaki feels “I can’t say anything specific about being a woman. I can’t say anything specific about being a writer. Fewer female writers are acknowledged here. I have male friends who say they can’t read female writers. But the female writers who get acknowledged make it in a big, significant, long-term way.”

“I’m a copywriter in an advertising agency. The advertising helps with my other writing. All these random ideas that can’t be part of a campaign but which end up in a story. This is what we take from the West and this is what we take from tradition and we sit with both.”

Ray started out as a poet and for a while wrote nothing else. “I think I feared exploring ideas further—keep it simple and vague so no one can ask too many questions. But I found there were stories that needed to be told that couldn’t be told in poetry.”

She started writing prose fiction four years ago, short, almost flash fiction-length pieces “that really fit into each other and have a quality that is similar.” She has enough stories now to fit into one project, “about how the past influences the present, and our inability to detach ourselves from the past. Some cultural ties can’t be broken.”

Most of Ray’s early reading was by Kenyan authors—YA books by Marjorie Oludhe Macgoye, or Grace Ogot, or the “Moses” series about a boy in Kenya by a white author whose name escapes Ray. “I also loved The Bride Who Wanted A Special Present by John Osogo.”

“The best comic I read in my childhood was Akokhan by Frank Odoi. It was brilliant. It took supernatural elements from folklore and used it in something like a Marvel comic.” (More information about Frank Odoi and Akokhan can be found here.)

“I’m still exploring, finding a voice and finding stories I want to tell. I’m no longer scared to explore.”

People I did not meet

Abdul Adan

His story “The Lifebloom Gift” was shortlisted for the 2016 Caine Prize, one of two speculative fiction stories nominated for this literary award. “The Lifebloom Gift” starts with a narrator who may suffer delusions and who believes himself transformed by Ted Lifebloom, a neurologically different individual who doesn’t believe anything exists unless he can touch it. There are other Lifebloomers whom Ted can activate—communicating through their moles. If the narrator is not entirely delusional, then this is a fantasy—once he is bloomed, his male nipples start to lactate. The story came about during Abdul’s time in St Louis working as a health transporter after having driven a woman home from hospital to a small town. On the porch, he saw her odd son who gave him the strangest, warmest smile. The writing style is a detached, ironical, and very funny—it could have been written by Donald Barthelme. The story is in part, he says, about the unearned gift of charisma, and how different people move at different speeds. Abdul is originally from Somalia, having lived many years in Kenya before coming to work in the USA, and seems to be something of an autodidact, citing Dostoyevsky and Nabokov among his favourite books. I met him at the Africa Writes conference in London in June of 2016, but didn’t succeed in getting an interview.

The Caine Prize nominated “The Lifebloom Gift” is available to read from their website. His story “Making Corrections” was first published in the journal African Writing and is available online at Arab Book World.

You can also read an interview with Abdul in The Mantle.

Alexis Teyie

is a 22-year-old Kenyan now studying History at Amherst College in the USA. She hoards poems and hopes her own poetry and speculative fiction will be worth saving someday. Her work is included in the Afrofuture(s) anthology and in the Language anthologies from Jalada. Her other SFF work appears in the 2016 anthology Imagine Africa 500, edited by Shadreck Chikoti. Her work has also featured in Q-Zine, This is Africa, African Youth Journals, and Black Girl Seeks, and the anthology Water: New Short Story Fiction from Africa.

Cherie Lindiwe, Denver Ochieng, Joel Tuganeio, and Marc Rigaudis

are the team behind Usoni, a Kenyan TV series in which volcanic ash darkens Europe, destroying agriculture. The result is a mass migration of refugees from Europe to Africa. Cherie Liniwe is the director, Denver Ochieng the editor and producer, Joel Tuganeio the writer. Marc Rigaudis, a French filmmaker resident in Kenya, is the creator of the series and is working on a feature film version; the trailer can be found here.

Jim Chuchu

Another member of the Nest co-operative, Jim Chuchu is not only the director of the banned These Are Our Stories but also several SFF-related films or projects. Read an interview with him here.

John Rugoiyo Gichuki

is a pioneer African SFF writer, winner of the 2006 BBC African Playwriting competition for his SF play Eternal, Forever, set in the United States of Africa 400 years from now, when the continent leads technological advances. He earlier won the BBC’s African Performance playwriting competition in 2004 with his play A Time For Cleansing, a play about incest and refugees in Rwanda.

Check out the BBC coverage of Eternal, Forever here.

Robert Mũnũku

A Nairobi-based writer who after my first visit started publishing, chapter by chapter, his SFF novel Zenith on his blog spot. You can read Chapter 1 here.

Sanya Noel

is the author of “Shadows, Mirrors And Flames,” a short story published in Omenana issue 2 (you can read the full story at the link.) It’s an unusual piece that combines magic with political torture told by a young girl who loves pulling the legs off locusts. Sanya’s bio describes him as “a Kenyan writer living in Nairobi. He works as a mechatronic engineer during the day and morphs into a writer at night. His works have previously been published in the Lawino magazine and the Storymoja blog. He writes poems, short stories and essays and loves eating apples in matatus on his way home.”

Wanuri Kahiu

is the writer director of the Science Fiction film Pumzi from 2009, screened at the Sundance Festival in 2010. She regards African science fiction as both an extension of traditional local beliefs that often include the future as well as the past and a reclaiming of both past and future from colonial influence. Online interviews with her can be found here and here

Endnote to Nairobi

So what is the connection between East African and experimental writing? Inspired by Clifton Cachagua’s love of the Beats, I re-read On The Road by Jack Kerouac.

Kerouac was from a French Canadian family, living in the United States. He grew up speaking a local language—the French-Canadian dialect of joual. He did not speak English fluently until he was six years old (in other words, when he needed it for a school). One can imagine he went through a school-enforced change of language similar to that experienced by many Kenyans.

The introduction to the Penguin Classics edition quotes a critic from Québec, Maurice Poteet, who feels that “Kerouac’s heroic efforts” to find his own language and technique of spontaneous prose “was a way to deal with bilingualism—the riddle of how to assimilate his first and most spontaneous language, joual, into a colloquial, American prose style.” The wordplay, the 120-foot long continual scroll of manuscript that let Kerouac write the first draft in a blind fervour, and the language experiments permitted him “to build bridges to and from a number of inner and local realities which might not otherwise ‘become’ American at all.”

In other words, spontaneous writing and effect are one answer, at least, to an ethnic situation that in many ways resembles the ‘double bind’ of psychology: if a writer cannot be himself in his work (a minority background) he is lost; if he becomes an ‘ethnic’ writer he is off on a tangent….

—Ann Charters quoting Maurice Poteet, Textes de L’Exode. Guérin littérature, 1987 from her introduction to On The Road, Penguin Modern Classics Kindle edition

Nothing can be proved, but it seems to me likely that East African writers are experiencing a similar linguistic stress.

If so, similar forces might be driving the urge to experiment. Some of the writers echo the Beat/Byronic/Wild Boys lifestyle as well. “I want hallucinogens,” said one of these authors with a smile. The writing shows no sign of needing them.

What is happening in Nairobi is a synthesis that learns from the stories and languages of local people, from science fiction, from experimental and literary Western fiction, and from new technology.

Back in London, I talked with visiting South African scholar Brenda Cooper, who nailed it for me:

“Referring to the stories that your grandmother tells you is another coded language. It is a gesture writers make to the inheritance of the wisdom of the past. It sounds like what you’re getting in Nairobi is a fusion, a syncretic form. Writers take inspiration from many different sources and domesticate them and make them fit for their own artistic purpose.”

The next question is—why don’t West African writers also empathize with the Beats and experimental writing? Nigeria, the home of Chinua Achebe and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, has anything from 200 to 400 or even more languages. Despite this linguistic stress, Nigerian literature is by and large classical in both language and form. Nigeria produced Fela Kuti, but his influence on prose fiction seems minimal.

The final instalment of this series will visit Nigeria where most African SFF writers live. It will talk with the founders of the African SFF magazine Omenana. Other instalments will interview writers and artists in Uganda and Malawi, and explore that other giant of African SFF, South Africa. Skype will reach more isolated writers in Rwanda and elsewhere, and at some point the series will publish results of a questionnaire of African SFF writers and readers.

Next, however, will be interviews with the diaspora in the UK.

Geoff Ryman has a Leverhulme Fellowship to study the rise of SFF in Africa and will be travelling to South Africa, Malawi, Uganda and Nigeria over the next year. He’s written SFF and mainstream novels and has won about 15 awards including the John W. Campbell Memorial Award, the Arthur C. Clarke Award (twice), the James W. Tiptree Memorial Award, the Philip K. Dick Memorial Award, and the British Science Fiction Association Award (twice) and the Canadian Sunburst Award (twice). In 2012 he won a Nebula Award for his Nigeria-set novelette “What We Found.” His novel Air was listed in The Guardian‘s 1000 Novels You Must Read. 253 is listed by Carmen Maria Machado on the Granta website as the best book of 1998. He administers the African Fantasy Reading Group on Facebook that has over 800 members.

Geoff Ryman can be contacted through Facebook by direct message. Request to join the African Fantasy Reading Group then befriend and send a direct message.